Core concepts

Fused lets teams run Python in the cloud without having to think about infrastructure. It's the glue layer between your most important data and the applications that consume the data.

If you're looking to simplify your life with serverless cloud, these pages will help you understand the patterns and best practices to work with Fused.

How does it work?

Fused takes your Python code and runs it in the cloud. Fused lets any of your tools run your code and load its output so you can easily move data across your different apps. This enables you to dramatically simplify your architecture and easily create integrations.

The UDF

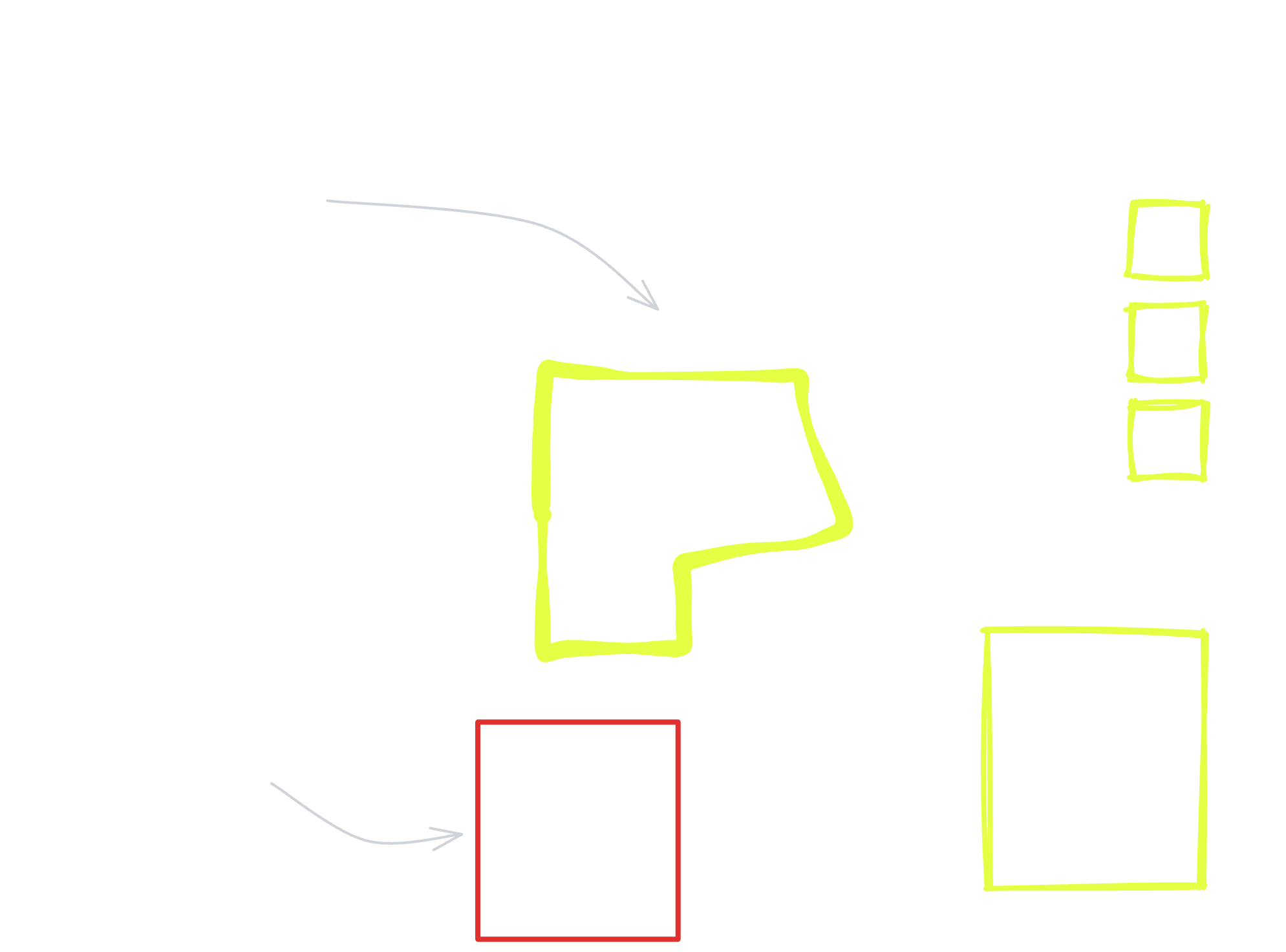

User Defined Functions (UDFs) are the core building blocks of Fused. They contain the Python code you want to run. As this diagram shows, the UDF code defines interactions with datasets and data platforms using standard Python libraries. Fused automagically creates a Hosted API endpoint for each of your UDFs. When an app calls the endpoint, Fused runs the UDF code on a serverless machine and returns the function output.

As a glue layer, UDFs integrate with your most important apps and can call each other (sequentially and in parallel) to assemble into complex workflows.

You can create and run UDFs on the Fused Workbench browser IDE or in any Python environment using the Fused Python SDK. When you save a UDF in Fused, you automatically get an endpoint for it which can be called by any tool that can make an HTTP request.

To write a UDF, its important to understand its anatomy. A UDF is a Python function with the following components, which the following sections describe at depth.

@fused.udf # a) Fused decorator

def udf( # b) Function declaration

bbox: fused.types.Bbox = None, # c) UDF parameters

table_path: str = "",

n: int=10

):

from utils import table_to_tile

gdf=table_to_tile(bbox, table=table_path)

return gdf # d) Return object

a) @fused.udf decorator

To create a UDF, decorate a Python function with @fused.udf. This decorator supercharges the function with the ability to run its code in a serverless cloud environment that automatically provisions and scales compute resources.

@fused.udf # a) Fused decorator

def udf():

...

return gdf

b) Function declaration

The next step is to structure the function's business logic to interact with upstream data sources and return an object which will be the UDF's output.

To illustrate, this UDF is a function called udf that returns a dataframe. Notice how import statements must be placed within the function declaration so they go wherever the function goes.

@fused.udf

def udf( # b) Function declaration

bbox: fused.types.Bbox = None,

table_path: str = "",

n: int=10

):

from utils import table_to_tile

gdf=table_to_tile(bbox, table=table_path)

return gdf

c) UDF parameters

When you call a UDF, you can choose to pass data to its parameters. This enables UDFs to dynamically run code based on its input parameters.

Explicit Typing

Fused resolves arguments to their specified types.

This is helpful when UDF endpoints are called via HTTP requests that specify argument values via query parameters, which require input parameters to be serializable.

For example, take a function like this one, with typed parameters.

@fused.udf

def udf(

bbox: fused.types.Bbox = None, # c) UDF parameters

table_path: str = "",

n: int=10

):

from utils import table_to_tile

gdf=table_to_tile(bbox, table=table_path)

return gdf

The bbox argument gives the UDF spatial awareness and users can decide its structure, for convenience - which you can read more about here.

When its endpoint is called like so, Fused injects a bbox parameter corresponding to a Tile with the 1,1,1 index, resolve table_path value as a string and the n value as an integer.

curl -XGET "https://app.fused.io/server/v1/realtime-shared/$SHARED_TOKEN/run/tiles/1/1/1?table_path=table.shp&n=4"

d) Return object

Like with a regular Python function, the UDF return statement makes a UDF function exit and hand back the return object to its caller.

@fused.udf

def udf():

...

return gdf # d) Return object

When writing a UDF, the data type and CRS of its returned object determines how it’ll appear on the map. To work with standard file and map services, Fused expects UDFs to return data in either raster or tabular vector formats.

Vector

Vectors represent real-world features with points, lines, and polygons. Fused accepts the following Vector return types:

gpd.GeoDataFramepd.DataFramegpd.GeoSeriespd.Seriesshapely geometry

Fused expects all spatial data in EPSG:4326 - WGS84 coordinates, using Latitude-Longitude units in decimal degrees. If the CRS of the returned object is not in EPSG:4326 CRS, Fused will make a best effort to convert it - so it's preferable that UDFs are written to return a data in the EPSG:4326 CRS.

Raster

Raster data is comprised of pixels with values, typically arranged in a grid. Rasters can have one or multiple layers.

Fused accepts the following Raster return types

numpy.ndarrayxarray.DataArraydatashader.transfer_functions.Imageio.BytesIO(including png images)

The returned raster object must have a geospatial component. This tells Fused where on the map to render it as an image. For example, this UDF returns an xarray DataArray, which inherently contains coordinates that tell Fused where on the map to place it. Verify this by printing the object and its type.

import fused

@fused.udf

def udf(lat=-10, lng=30, dataset='general', version='1.5.4'):

import rioxarray

lat2= int(lat//10)*10

lng2 = int(lng//10)*10

cog_url = f"s3://dataforgood-fb-data/hrsl-cogs/hrsl_{dataset}/v1.5/cog_globallat_{lat2}_lon_{lng2}_{dataset}-v{version}.tif"

rds = rioxarray.open_rasterio(

cog_url,

masked=True,

overview_level=4

)

# Show the output type

print(type(rds))

# Inspect the output object

print(rds)

return rds

The print statements above should display the following in the stdout box, which shows how the layer value and coordinates of the DataArray object.

<class 'xarray.core.dataarray.DataArray'>

<xarray.DataArray (band: 1, y: 1126, x: 1126)>

[1267876 values with dtype=float64]

Coordinates:

* band (band) int64 1

* x (x) float64 30.0 30.01 30.02 30.03 ... 39.97 39.98 39.99 40.0

* y (y) float64 -0.0001389 -0.009028 -0.01792 ... -9.991 -10.0

spatial_ref int64 0

Attributes:

AREA_OR_POINT: Area

scale_factor: 1.0

add_offset: 0.0

💡 There's 2 ways to control the transparency of raster images.

- In RGB images, the color black (0,0,0) is automatically set to full transparency.

- If a 4 channel array is passed, i.e. RGBA, the value of the 4th channel is the transparency.

When returning a raster object that doesn’t have spatial metadata, like a numpy array, the UDF must return the object's bounds to tell Fused where to place it on the map. For example:

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.Bbox=None):

...

return np.array([[…], […]]), bbox

If you forget to pass the bounds, Fused will default its bounds to (-180, -90, 180, 90) and the output image will expand to the size of the globe.

Execution modes

Fused automatically creates an endpoint for all saved Fused UDFs. When a client application calls a UDF endpoint, Fused runs a lightweight serverless Python operation and returns the function output. A call to a Fused UDF endpoint can return data as if it were a single remote File. The same endpoint can be called dynamically, as Tile, so it interoperates with map tiling systems.

File & Tile

To understand how a Fused UDF can be configured to execute, it's important to first understand the difference between File and Tile data.

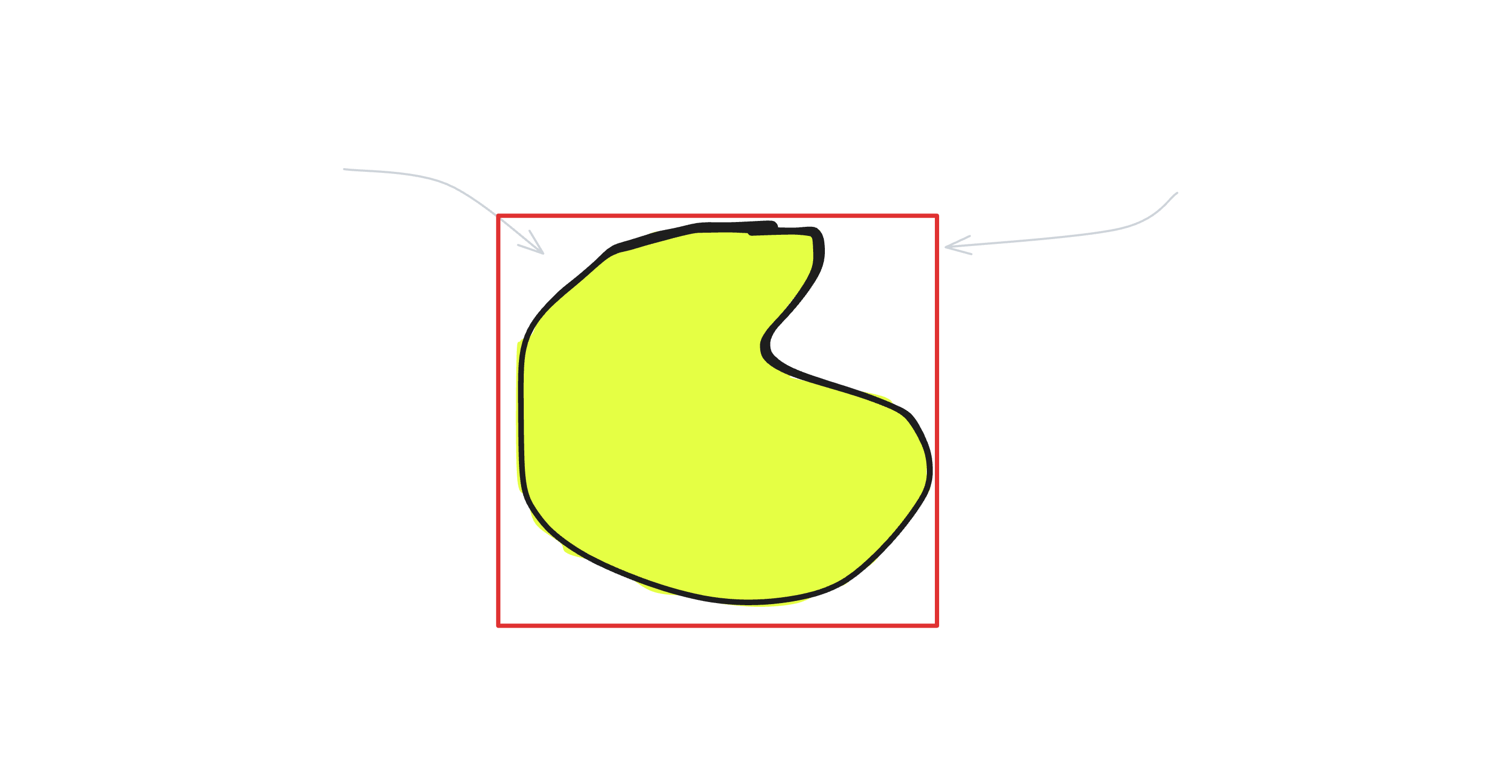

Consider this diagram. When loaded as a remote File, every coordinate of the complex polygon would be included in one single file. In a Tiled format, there are predefined tile sets (grids) and the geometry is split into one or more Files, where each File represents one cell of the grid.

Loading or rendering an entire dataset is an expensive operation in part because of the data volume that must transfer across the network. Fused UDFs can be designed to automatically split and output a dataset across several Tiles - and speed up computation by operating on each part of the dataset in parallel.

File

When an endpoint is called as a File, the UDF runs only once and returns all output data in a single batch. This behaves like the access pattern for a remote file URL.

Tile

When and endpoint is called as a Tile, the endpoint becomes interoperable with map tiling clients. The endpoint is called as a File for every Tile requested, and Fused dynamically passes a bbox object to each UDF call corresponding to the index of each tile on the map.

The bbox object

A UDF can strategically leverage cloud-optimized data formats and effeciently load only a fraction of a dataset. A UDF becomes spatially aware when it leverages the bbox parameter to spatially filter the datasets it operates on. This way, Fused distributes execution across multiple workers that scale and wind down as needed. Tile-level spatial filtering supercharges UDFs to process only specific parts of a dataset - based on specified geographic or logical partitions.

The growing popularity of cloud optimized data formats is revolutionizing data processing by eliminating the need for specialized hardware to handle large datasets. For further reading on data formats, refer to resources on: Cloud Optimized GeoTiff, Geoparquet, and GeoArrow.

Tile mapping tools call Fused endpoints and dynamically pass an XYZ index for each Tile to render. When a UDF endpoint is called this way - in Tile mode - Fused passes the UDF a bbox object as the first parameter. This object is a data structure with information that corresponds to the Tile's bounds and/or XYZ coordinates. The object is named bbox by convention, but it's possible to use a different name as long as it's in the first parameter.

For convenience, users can decide the structure of the bbox object by setting explicit typing. The 3 available structures are:

fused.types.TileGDF

This is a geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame with x, y, z, and geometry columns.

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.TileGDF=None):

print(bbox)

return bbox

>>> x y z geometry

>>> 0 327 790 11 POLYGON ((-122.0 37.0, -122.0 37.1, -122.1 37.1, -122.1 37.0, -122.0 37.0))

fused.types.Bbox

This is a shapely.geometry.polygon.Polygon corresponding to the Tile's bounds.

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.Bbox=None):

print(bbox)

return bbox

>>> POLYGON ((-122.0 37.0, -122.0 37.1, -122.1 37.1, -122.1 37.0, -122.0 37.0))

fused.types.TileXYZ

This is a mercantile.Tile object with values for the x, y, and z Tile indices.

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.TileXYZ=None):

print(bbox)

return bbox

>>> Tile(x=328, y=790, z=11)

If the UDF is called as a File, Fused does not pass a bbox parameter. To write UDFs so they can be called in either execution mode, Fused recommends setting the bbox as the first parameter, and typing it as a fused.types.Bbox with a default value of None. This will enable the UDF to run in both as File (when bbox isn’t necessarily passed) and as a Tile. For example:

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.Bbox=None):

...

return ...

When using the Fused Workbench, a UDF can be configured to render as "Auto" so Workbench automatically handles the output as Tile if it statically checks that the above types are used in the UDF. Otherwise, it assumes File.

UDFs called via the Fused Python SDK or HTTP requests run as Tile only if a parameter specifies the Tile geometry.

Examples of using the bbox object

a) Spatially filter raster files

The Fused utility function utils.mosaic_tiff and pystac-client's catalog.search illustrate how to use bbox to spatially filter a dataset.

For example, function utils.mosaic_tiff generates a mosaic image from a list of TIFF files. bbox defines the area of interest within the list of TIFF files set by tiff_list.

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.TileGDF=None):

utils = fused.load("https://github.com/fusedio/udfs/tree/f928ee1/public/common/").utils

data = utils.mosaic_tiff(

bbox=bbox,

tiff_list=tiff_list,

output_shape=(256, 256),

)

As an example, the LULC_Tile UDF uses mosaic_tiff to create a mosaic from a set of Land Cover tiffs.

Spatially filter STAC datasets

STAC (SpatioTemporal Asset Catalog) datasets can be queried by passing the bounding box’s bounds (bbox.bounds) to the pystac client of the Python pystac-client library.

@fused.udf

def udf(bbox: fused.types.TileGDF=None):

import pystac_client

from pystac.extensions.eo import EOExtension as eo

catalog = pystac_client.Client.open(

"https://planetarycomputer.microsoft.com/api/stac/v1",

modifier=planetary_computer.sign_inplace,

)

items = catalog.search(

collections=[collection],

bbox=bbox.total_bounds,

).item_collection()

Call a UDF endpoint

File

By default, a UDF runs as File - it executes once and returns a single output that corresponds to the input parameters. The UDF endpoint behaves like a remote file in that calling it returns a single batch of data - but the endpoint also accepts parameters that dynamically influence the UDF's execution.

https://www.fused.io/server/.../run/file?dtype_out_vector=csv

This enables client applications to make an HTTP request and load the UDF's output data into the tool that makes the call.

Note that files are downloaded entirely - even if the data is requested as a Parquet.

Tile

The same UDF's API endpoint can be called to run like a Tile. This makes it possible for Fused to serve vector or raster tiles into industry standard tools that work with tiled web maps - think Leaflet, Mapbox, Foursquare Studio, Lonboard, and beyond.

https://www.fused.io/server/.../run/tiles/{z}/{x}/{y}?&dtype_out_vector=csv

Tiling clients can make dozens of simultaneous calls to the Fused API endpoint - one for each tile - and seamlessly stitch the outputs to render a map. Instead of operating on an entire dataset, Fused only acts on the data that corresponds to the area visible in the current viewport.

You can read more about the XYZ indexing system in the Deck.gl documentation. In fact, Fused Workbench runs UDFs on a serverless backend and renders output in Deck.gl.